Ulcerative colitis is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that results in inflammation of the rectum and colon. It is not common, occurring in 5 per 100,000 of the Australian population. It most commonly has its onset in early adulthood (second and fourth decade), but can occur at any age.

Cause

The exact cause of ulcerative colitis is not known; however, many theories exist. It does not appear to be due to an infectious agent, and there is no direct single genetic mutation that is responsible. However, clusters of ulcerative colitis do exist within families, suggesting that genetics is perhaps one of many factors involved.

Site of involvement

In ulcerative colitis, the rectum is always involved causing proctitis. This involvement may extend further than this to involve the last bit of colon, or even the entire colon (pancolitis). Ulcerative colitis always causes confluent disease, meaning that there are not patches of health colon between patches unhealthy colon as is seen in Crohn’s disease. Ulcerative colitis only involves the large bowel, and cannot involve the upper gastrointestinal tract (UGIT).

Presentation

Inflammation of the inner lining of the bowel (mucosa) results in inflammation and shallow ulceration which causes diarrhoea often quite bloody, with associated mucous (dysentery). If this is longstanding, loss of blood and protein can result in anaemia and weight loss, as well as generalised fatigue.

Extra-intestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis usually only affects the colon, but occasionally, it can affect the liver causing jaundice (sclerosing cholangitis), or affect the eyes causing inflammation (iritis), or cause arthritis and skin rashes (erythema nodosum) or ulcers that fail to heal (pyoderma gangrenosum). Patients with ulcerative colitis have 5.6 times the chance of colorectal cancer than the normal population. Those with extensive inflammation of their entire colon (pancolitis) are at the greatest risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Symptoms

Bloody diarrhoea with mucus is the main feature of ulcerative colitis. There may be weight loss, or abdominal pains in severe cases. The typical course of ulcerative colitis is for the condition to “wax and wane” with exacerbations often followed by periods of remission.

How is ulcerative colitis diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on colonoscopy, with full inspection of the colon and rectum. Colonoscopy also allows for biopsies to be taken of the colon and rectum, which are then reviewed under a microscope to determine the diagnosis. In the early stages of the disease, making a definite diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is sometimes difference, and the term “indeterminate colitis” is used. There is no single blood test to diagnose ulcerative colitis, however a number of blood tests including White Cell Count and inflammatory markers often support the diagnosis of an acute attack of ulcerative colitis

Medical treatment of ulcerative colitis

Medications for treating ulcerative colitis include those used for well controlled disease to maintain the disease of which salazopyrine and mesalazine are most commonly used. Sometimes a slightly stronger drug azathioprine (Imuran®) is needed. For acute attacks or “flare-ups” anti-inflammatory drugs such as hydrocortisone and prednisone are necessary. These can be applied directly to the rectum in the form of enemas (Predsol®) or as foams (Salofalk®), or taken systemically, either intravenously (hydrocortisone) or orally as a table (prednisone).

Cure for ulcerative colitis

Unfortunately, there is no known cure for ulcerative colitis other than surgical removal of the large bowel. Colonoscopy, to view the rectum and large bowel and to allow biopsies to be taken to check for pre-cancerous or cancerous changes, are important and should be done every 3-5 years.

Surgery for ulcerative colitis

Surgery is indicated when medical treatment has failed, and can no longer control the symptoms that prevent a normal lifestyle. Surgery is also indicated if the side-effects of long-term medications are creating complications. Surgery is sometimes needed if there is cancer or risk of cancer. Emergency surgery to remove the colon is occasionally needed when the disease is out of control.

Removal of colon and rectum

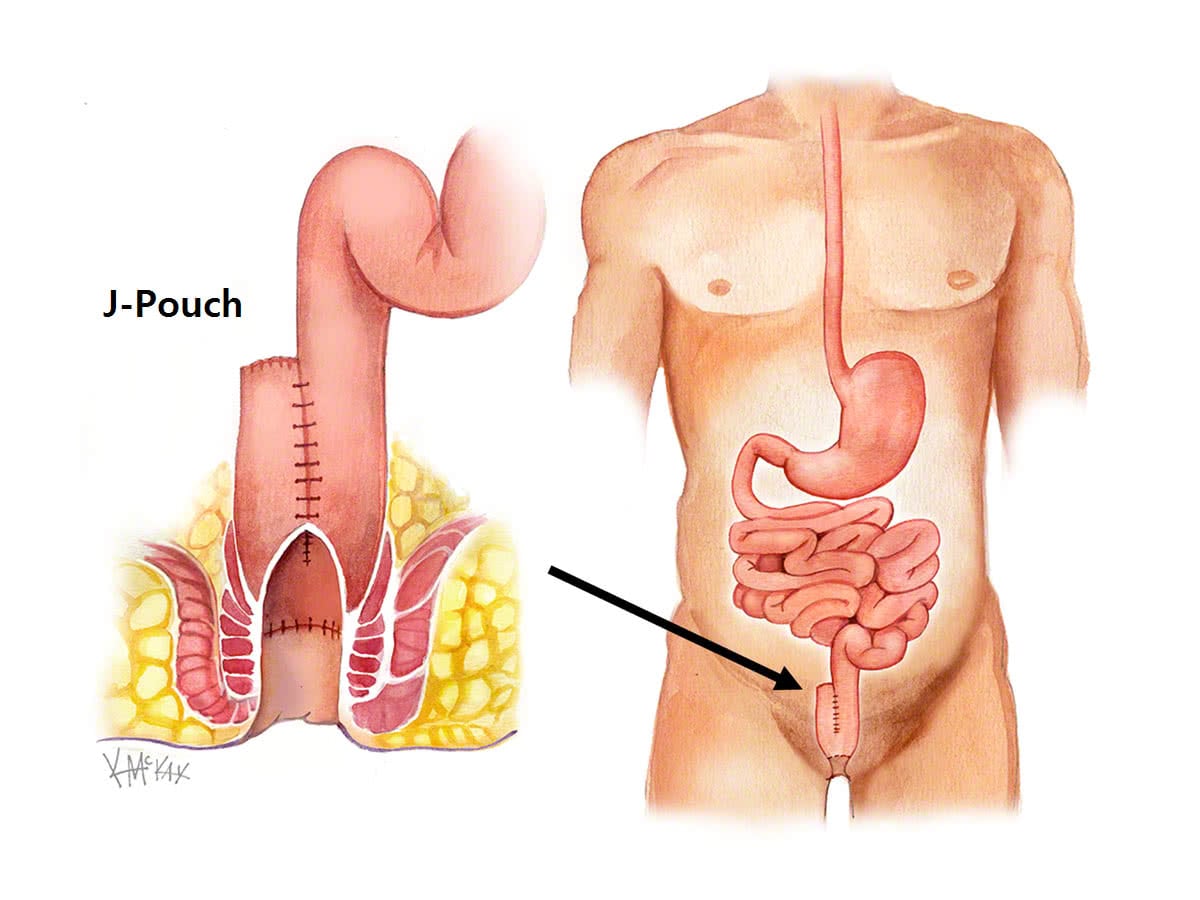

Removal of the colon and rectum (procto-colectomy) aims to remove the risk of further attacks of ulcerative colitis, as well as remove the risk of colorectal cancer. This operation almost always requires a temporary stoma (ileostomy) for 3 months. The colon and rectum can be removed together in the well-controlled patient with restoration of bowel continuity with the creation of a J-Pouch. However, in the unwell patient, it is preferable to only remove the diseased colon acutely, and to restore continuity in the form of a J Pouch 3-6 months later when the disease is medically controlled.

Pouch surgery

To allow for removal of the rectum, a new rectum is constructed using small bowel (called a “J-Pouch”).

When to operate?

The decision to operate will depend on a number of factors. Involvement of you, your GP, gastroenterologist and a colorectal surgeon is important in making this decision.

Impact of surgery on lifestyle

The symptoms of ulcerative colitis can be eliminated with surgery that removes the colon and rectum. This can allow all medication to be stopped. A stoma is frequently needed, and in most cases this is temporary. In expert hands, rectal surgery can now be performed safely minimising the risk of damage to nerves necessary for a normal sex life and pregnancy. However, surgical removal of the rectum carries a risk of impotence and ejeculatory problems in men[1], and infertility [2] and altered sexual function in women[1], and this needs careful consideration and discussion with your colorectal surgeon prior to pouch surgery. J-Pouch surgery allows defecation through the anus, however some degree of diarrhoea is common, with up to 6-7 loose stools a day not uncommonly reported. In most cases, quality of life improves after pouch surgery [3-5]. Inflammation or infection of the pouch, referred to as “Pouchitis”, occurs acutely in up to 15% of cases and usually responds to antibiotics. Chronic more troublesome pouchitis resistant to antibiotics occurs in approximately 5% of cases.

What to expect pre and post operatively for surgery for ulcerative colitis

You will need to have only clear fluids the day before your surgery. Clear liquids are those that one can see through. When a clear liquid is in a container such as a bowl or glass, the container is visible through the substance. You will also require bowel prep to clean your colon. Take a pico-sulfate (Picolax®) at 2pm and 6pm the day before your procedure. You need to fast from midnight the night before if your surgery is scheduled for the morning, or from 6am if scheduled for the afternoon. Immediately after your procedure you will be commenced on free fluids (semi thickened fluids such as custard, yoghurt, thin porridge). If your procedure is performed laparoscopically, you will be up and mobilising from day one. You will be commenced on a light diet once you have passed flatus. You will be discharged from hospital once you have opened your bowels. A typical admission is anywhere from 3 days to 7 days.

You will need to see your gastroenterologist and colorectal surgeon at 3-6 weeks post-operatively to check on you progress.

References

- Lange MM, Marijnen CAM, Maas CP et al. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1578-88

- Johnson P, Richard C, Ravid A et al. Female infertility after Ilea Pouch-Anal Anastomosis for Ulcerative Colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1119-26.

- Lillehei CW. Masek BJ. Shamberger RC. Prospective study of health-related quality of life and restorative proctocolectomy in children. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 53(10):1388-92, 2010 Oct.

- Ganschow P. Pfeiffer U. Hinz U. Leowardi C. Herfarth C. Kadmon M. Quality of life ten and more years after restorative proctocolectomy for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis coli. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 53(10):1381-7, 2010 Oct.

- Berndtsson IE. Carlsson EK. Persson EI. Lindholm EA. Long-term adjustment to living with an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 54(2):193-9, 2011 Feb.