The Australian NHMRC guidelines advise that radiotherapy be given for all large rectal cancers that are extending into the muscle wall of the rectum (T3,T4) or that have evidence of lymph node spread on MRI or ultrasound (N1). In this situation, even with good surgery there is a 5-10% risk of local recurrence of the cancer in the first 5 years after surgery. This can be halved by giving radiotherapy before surgery (neoadjuvant radiotherapy) [1-3]

Staging of rectal cancer

Once a diagnosis of rectal cancer is made, the size and spread of your cancer can be estimated by doing a number of scans. A CT scan will be performed to determine the size of the rectal cancer and to determine if there are any obvious features to suggest spread (metastasis) to glands (lymph nodes) or elsewhere (liver, lung or bones). If there is no spread (metastasis) to liver, lung or bones, and the rectal cancer involves the last 2/3 of the rectum, then a rectal ultrasound or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan may be performed. The only definitive way of determining the extent of spread of your tumour is by examination under a microscope (histopathological examination) of the tumour after surgery.

Rectal ultrasound

Rectal ultrasound involves insertion of a small ultrasound probe about the size of a finger into the rectum to acquire real-time images of the tumour. It is useful for early tumours which have not yet spread into the muscle of the rectum (called “T1” or “T2” rectal tumours).

MRI

MRI with contrast injection (gadolinium) will determine the size of the cancer as well as whether or not it has spread to nearby lymph nodes. If the cancer has spread to local lymph nodes, a positive MRI result will be accurate in only 70% of cases (false negative report will occur in 30% of cases)[4]. If the cancer has not spread to lymph nodes, it will tell you this with an accuracy of 95% (false positive report will occur in 5% of cases). It will also tell you with 95% certainty if the perimeter of the rectum (circumferential radial margin) is free of tumour.[5]

Histopathology

The only reliable test to determine the spread (staging) of rectal cancer is by examining the specimen under the microscope (histopathological examination), after your surgery. This gives exact accurate information about the spread of the tumour locally and to lymph nodes. This is a lengthy procedure and results will usually not be available for at least 5 days following your surgery.

Which rectal cancers get radiotherapy before surgery?

Rectal cancers involving the lower 2/3 of the rectum (last 10cm) which on ultrasound or MRI are seen to extend into the muscle wall of the rectum (T3,T4) or surrounding lymph nodes (N1) which have not already spread (metastasised) to other organs (such as liver, lung and bone) are potentially curable and will need pre-operative (neoadjuvant) radiotherapy prior to surgery.

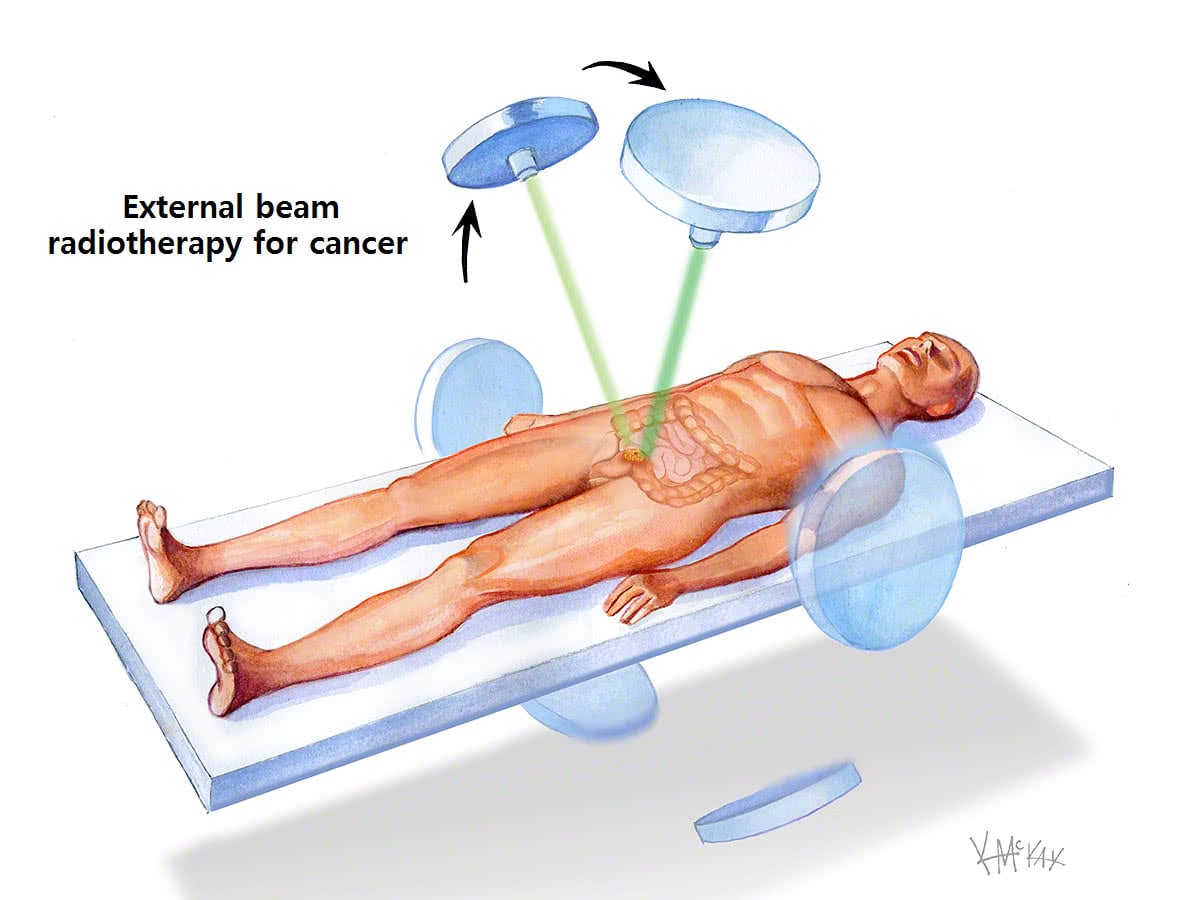

Types of delivery of radiotherapy

Radiotherapy delivered before surgery (pre-operatively) is preferable to radiotherapy delivered after surgery, as it causes fewer side effects. [1-3]

A small dose of radiotherapy (25Gy) can be given quickly over 5 days (short-course radiotherapy), or can be given as a large dose of radiotherapy (50Gy) delivered slowly over 5 weeks (long course radiotherapy). Currently the evidence suggests that short course and long course radiotherapy are equivalent in efficacy with regard to preventing local recurrence, [6-8], however for lower and larger tumours long-course radiotherapy may have the advantage resulting in fewer permanent stomas [8].

As a rough rule of thumb, pre-operative short-course radiotherapy is generally given if CT or MRI suggest one of the following:

- Rectal cancer is moderately large and has already begun to invade the muscle wall of the rectum (called a “T3” cancer); or

- Rectal cancer has spread to 1-3 nearby lymph nodes (called an “N1” cancer)

Pre-operative long-course radiotherapy over 6 weeks is generally given if CT or MRI suggest one of the following:

- Rectal cancer is large and has already broken through the muscle wall of the rectum (called a “T4” cancer); or

- Rectal cancer is has spread to more than 3 nearby lymph nodes (called an “N2” cancer)

Short-course radiotherapy

Short course radiotherapy delivers 25Gy of radiation over 5 days (5Gy each day). Best results are achieved when surgery is performed within 1-2 weeks of completing radiotherapy.[8]

Long-course radiotherapy

Long course radiotherapy delivers 50Gy of radiotherapy over 6 weeks. Best results are achieved when surgery is performed 6-8 weeks following the completion of radiotherapy to allow the swelling and inflammation to settle.[9-10] A small dose of chemotherapy with also be given with the radiotherapy prior to surgery as it improves the action of radiotherapy (chemo sensitiser). After surgery, the remainder of the chemotherapy will be given over 6 months.

Post-operative radiotherapy

Post-operative radiotherapy is occasionally indicated when pre-operative radiotherapy was not given, and microscopic examination of the tumour after it has been removed shows advanced disease. The complications of receiving radiotherapy after surgery include poor rectal function, faecal incontinence, and injury to small bowel. These complications need to be discussed with your colorectal surgeon and radiation oncologist.

References

- Hyams DM, Mamounas EP, Petrelli N et al. A clinical trial to evaluate the worth of preoperative multimodality therapy in patients with operable carcinoma of the rectum: a progress report of National Surgical Breast and Bowel Project Protocol R-03. Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:131-9

- Colorectal Cancer Collaborative Group: Adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic overview of 8507 patients from 22 randomised trials. Lancet 2001;358:1291-1304

- Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1731-1740

- Lambregts DM. Beets GL. Maas M. et al. Accuracy of gadofosveset-enhanced MRI for nodal staging and restaging in rectal cancer. Annals of Surgery. 253(3):539-45, 2011 Mar.

- The MERCURY Study group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ 2006: 333;779.

- Ngan S, Fisher R, Goldstein M et al. A randomized trial comparing local recurrence (LR) rates between shortcourse (SC) and long-course (LC) preoperative radiotherapy (RT) for clinical T3 rectal cancer: An intergroup trial (TROG, AGITG, CSSANZ, RACS) J Clin Oncol 2010;28(Suppl.15):3509

- Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A et al. Long term results of a randomized trial comparing preoperative short-course radiotherapy with preoperative conventionally fractionated chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2006; 93:1215-1223

- Pettersson D, Cedermark B, Holm T et al. Interim analysis of the Stockholm III trial of preoperative radiotherapy regimens for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:580-587

- Moore HG, Gittleman AE, Minsky BD et al. Rate of pathologic complete response with increased interval between preoperative combined modality therapy and rectal cancer resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47:279-286.

- Francois Y, Nemoz CJ, Baulieux J et al. Influence of the interval between preoperative radiation therapy and surgery on downstaging and on the rate of sphincter sparing surgery for rectal cancer: the Lyon R90-01 randomised trial. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2396-2402.